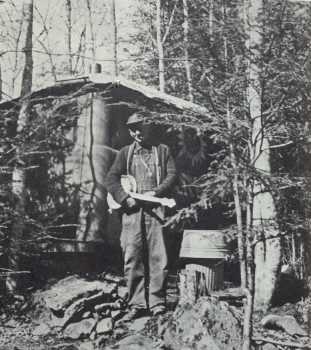

Daniel Manous, American Hermit (ca. 1970)

--

with reflections by his granddaughter

In the series of books about Appalachian Mountains life and lore, the Foxfire

book series, the first volume records the story of Daniel Manous, called "a

loner." He lives near Franklin, North Carolina, in an abandoned bread truck with

a wood stove and bed, working at a nearby fish hatchery. Manous owns two books

(poetry of Burns and of Tennyson), and spends free time hiking, hunting, and

playing a banjo (see picture).

Manous tells the story of a preacher in the mountains who had a snake in a box, which he placed on the pulpit whenever he preached. The preacher claimed to have the snake handy in case God wanted to test his faith. One day, he felt that call and reached into the box in the middle of the service. He pulled out the snake without effect -- the snake remained as calm as could be. Later, however, the people wanted him to do it again. Though he was reluctant, they kept urging him, so he did it. He reached into the box. This time he was bitten. "He lived, but just." The preacher concluded that he was not bitten the first time because he had done what God wanted him to do, but he was bitten the second time because he had done what people wanted him to do.

A good enough lesson for a hermit, one might add.

¶

The following reflections by Julie Maureen Daniels, granddaughter of Daniel Manous, were sent to Hermitary as a private message. We thought it compelling enough to want to share it with Hermitary readers and requested Julie's permission to reprint the message here. She graciously agreed.

I am the daughter of Mary Naomi Manous and granddaughter of Daniel Manous and am, myself, a recovering hermit.

While I have struggled to overcome a crippling sense of isolation born of fear and mistrust, I have also worked to retain the reality of autonomy, the gift of solitude.

To see my grandfather lauded for his isolationism is a bit queer. His was not such a simple story.

He was a troubled and lonely man; his love of solitude, his love of his native North Carolina mountains, his land, his ways, was equaled by his love for his five children and wife he left behind to return (from Greenville, South Carolina) to that bread truck.

A bread truck, by the way, which was afforded him as a benefit of his job, to monitor the lands surrounding Betty's Creek -- a job which paid very little, and if it did not provide for his ailing health and his most basic needs (heat, medicine), at a minimum, he could live the life he had been raised to live -- that of an Appalachian boy raised in the woods, taught to catch and kill his own food, who knew little else (literature and music, unfortunately, have never been practical).

Essentially, when he and my grandmother sold their land to the asbestos mines and moved to the "big city" of Greenville, my grandfather could not deal with the city ways. He could not get a job and returned, alone, leaving behind his wife and five children.

It came time for him to leave my grandmother, to resolve, in his way, their marital problems, the problem of their butting intellects, her need to work outside home and land, the degradation of having to sell the land (dozens of acres) which had been in his family for generations -- land outside Highlands, North Carolina, which is now worth millions.

Poverty drove Daniel Manous to sell his family land. Poverty kept him on Betty's Creek, in a bread truck, his only riches music, literature and nature.

Emotional strife was the wedge between himself and his family. Neither of these two factors, pain and poverty, are to be glorified.

God's green earth was his only home, and I wonder about his thoughts when alone in a snow storm leaning towards his wood stove. Certainly a flake of the swirl of life's experiences would sometimes enter his mind ... his daughters and his son; Ovaline Susan who worked along side him for over twenty years, bore his children, lived with him in austerity; his father and mother who raised him in the very same poverty; his many brothers and sisters; a childhood friend -- someone.

Humans are never alone with memory.

Daniel Manous, my grandfather, was a good man. But he was also a sad and lonely man.

This is the difference between "hermitting" and solitude.

I just wanted to make that clear.

As for Grandpa's granddaughter, I have finally secured myself three acres in

rural Georgia, three-fourths of it forested. I have a yurt hidden deep within

the woodline. It is clear to everyone in my life that this is my space, my

retreat and that I am not to be disturbed when there.

My yurt has electricity, a small fridge, a hotplate, my wee library, a desk and a chair.

But, I always return -- return to my responsibilities to others, responsibilities that I, myself, have cultivated, despite my solitary nature. I return to balance myself, to remind myself that I am whole, self-sustaining, yet interdependent, one of many and entirely individual, simultaneously.

Grandpa and Grandma could not afford such a luxury; indeed, such willful autonomy was not possible for either men or women then, particularly when so impoverished.

My grandparents' dire poverty was accompanied by emotional illness, as is quite common: the mental turbulence met when hunger is constant; anger and fear over that hunger; anger and fear at not being able to care for one's children, much less oneself; humiliation and a lack of education and therefore opportunity, therefore any hope of getting out. Physical, emotional, verbal and sexual abuse.

Desperate people barely surviving, anger and pain raging, mixed in with all the beauty and good, all the poetry, music, botany, mountain wisdom and religiosity. Tilly Olsen said that the definition of oppression is the lack of options. My grandparents had no options, no hope.

Daniel Manous, my grandpa, never returned to the responsibilities he consciously, willfully, cultivated.

The absence of hope was a way of being for both himself and grandma. This is the legacy they passed on to their children, to my mother, aunts and uncle. Grandpa stopped talking to his wife and children over a decade before he left them physically, embracing a solitary existence. This seems like historical fiction for the uninformed, but it is a painful reality for those he left in his path, most specifically, his children. And Daniel Manous' children, in turn, passed this fear (warranted or not) on to their children, along with the anger and the abuse.

The question is not about Grandpa's right to live a solitary existence, but how he went about it: what it really meant.

Daniel Manous was not embracing nature and God when he isolated himself; he was running away, abandoning his life, a life that included vulnerable young children who depended on him not only for food and shelter but most importantly for the development of their own self-worth.

If Grandpa were alive today, I would give him my yurt. I would make sure he had his medicine. I would let him hunt and fish on my land, and I would leave him be for as long as he liked, for years if he wanted, for the rest of his days.

But before doing so I would require him to give an explanation before his departure. I would require him to write a love letter to each of his children, saying goodbye, telling them that this death by abandonment was not a reflection on their worthiness but a self-imposed exile entirely of his own doing, a result of his own transgressions, not theirs.

Grandpa punished himself. My God, how that man must have hurt. His children never understood this and took his living death, what so many call solitude, as an affront to their very existence. This was all due to the vast difference between solitude and isolation and is unfortunately the family legacy Daniel Manous passed along.

A legacy of not just music, literature, wisdom, and a respect and knowledge of nature but also of fear, anger, sorrow, fragmentation, and separation.

If Daniel Manous were living alone and hidden on my three wooded acres with the understanding that he was "just that way", if he had said goodbye and explained his departure, then perhaps all the hurt would have been easier to absorb. His children would at least have the understanding that their Daddy was just a hermit and that didn't mean they were not worthy of his love, therefore, of their own existence. Maybe his children would be closer to their own children.

I have always missed you, Grandpa. I saw you once as a very small child and then much later in your casket. It makes me angry and sad to only learn of you in books. I miss you.

I miss you, Grandma. Thank you for the peanut butter sandwiches and for letting us jump on the bed.

I miss you, Mama. Thank you for teaching me about the civil rights movement and for taking me to see "Unto These Hills" and for teaching me about centipedes.

This is an open letter to the Universe.

Sincerely,

Julie Maureen Daniels

P.S. Mama knows all this better -- best -- but I am just my lone self, all I can be: a granddaughter and a daughter feeling my oldest bones, a collective of life experience, stories, and profound love for my family, past, present and future.

¶