Blindness is both a condition and, in popular speech, a metaphor. The blind person cannot see, while the metaphor makes blindness both a virtue and a a stigma. Justice is blind, it will be said, and a just person does not weigh appearance or visual details when making a moral judgment. At the same time, to be blind can be a metaphor for stubborn ignorance, as in the saying that there is none so blind as one who cannot see, or does not want to see, or when someone rants at another about missing something obvious in a task or an argument: “How could you be so blind!” or “Are you blind?”

Clearly, common speech and metaphor has not yet sorted out the difference between physical condition and mental ones, as words like lame and dumb are still widely used for multiple meanings.

A classic literary presentation of blindness is in the Mary Shelley character of De Lacey in her novel Frankenstein. The plot revolves around the “monster” that scientist Dr. Frankenstein has created but now rues with a compelling desire to destroy it. The “monster” represents the outsider, the persecuted, the ugly and repulsive to all he encounters, with evil intent ascribed to his mere appearance though he is originally without “sin” or harmful desire. One night the monster enters the DeLacey house. The family is away except the blind DeLacey, who sits alone in the parlor.

The monster apologizes for the intrusion and tells him:

I am an unfortunate and deserted creature. I look around and I have no relation or friend upon earth. … I am an outcast in the world forever.

After more conversation on the subject wherein the monster seeks the kindness of none other than De Lacey’s family, described obliquely, the old gentleman replies:

I am blind and cannot judge of your countenance, but thesre is something in your words which persuades me that you are sincere.

Reassured, the monster thanks DeLacey for his kindness and aid, hoping thereby that “I shall not be driven from the society and sympathy of your fellow creatures.” DeLacey responds that even if this visitor was hunted as a criminal, it would not abrogate his humanity and virtue as a person.

Two ironies emerge: first, that DeLacey himself is a political exile and deemed a criminal because of his revolutionary politics, and, second, that the monster is unreflectively placed by DeLacey in the company of human beings identified with entitlement to beneficence, when the source of his origin as a creature is at issue: his humanity or lack of it, his acursed existence and animosity toward his creator who made him so flawed. Thus the monster’s plight and DeLacey’s blindness are aspects of the same flawed humanity.

Shelley’s views are romantic but morally charged. English poet John Milton, writing centuries earlier, went blind in adulthood but bargained in his own manner for his Lord’s grace against the unassuming fictional DeLacey, even less Frankenstein’s monster. Milton in his poem “On His Blindness” credits his patience with affliction a source of redeeming virtue for him. At the same time one senses in Milton’s verbal demurring from resentment the suggestion that God’s blindness itself is the true moral issue at hand.

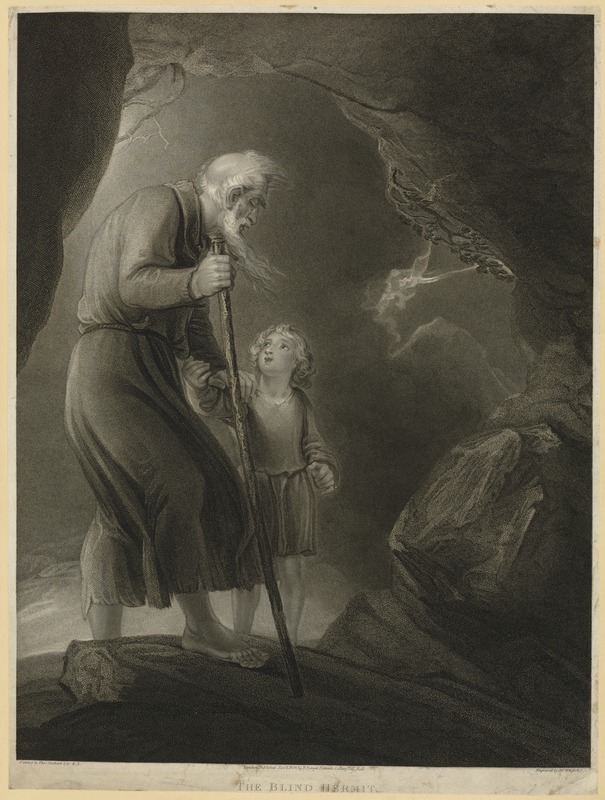

A curious case of a blind hermit depicted in art is a painting by the British painter Thomas Stothard (1755-1834). The painting, held by the Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts (U.S.), is conventionally labeled “Blind Hermit” by most sources. But in fact the painting is “Belisarius the Blind,” depicting an event in Byzantine history — dubious in having been written five centuries after the supposed event. Belisarius was the outstanding conqueror-general of Emperor Justinian, whose suspicions were aroused by his general’s successes and presumed ambitions. Upon returnng to the capital, Justinian had Belisarius blinded and cast out as a beggar. Undoubtedly, however, the portrait easily evokes a hermit, and his young helper an angelic presence.

Stothard’s painting, too, may evoke Tobit of the Old Testament and his son, though his son was older by the time of his father’s blindness, and the old man Tobit is not a hermit but a doublet of Job, even to his complaints against God, who has done this to him.

The American engraver William French (1815-1898) also created a blind hermit with young guide, sentimental and stylized, closly parallel to Stothard, enough to sugget imitation. His blind hermit has no classical robe, however, and is less ambigously a medieval monk, complete with beads. French’s work is also held by the Perkins School.

The suggestive incapacity of blindness coupled with the near-outcast status of the hermit makes an image of pathos, especially when assigned a story of past success, as in the depiction by Stothard. In the imaginative novel The Bee-loud Glade of American writer Steve Himmer, the protagonist drops out of the rat race to become a decorative hermit but grows nearly blind as he ages, now become a true hermit living in concealment and solitude. Incapacity pursues everyone who ages, but for the hermit the challenge is greater. This writer knows because double vision and glaucoma slow his pace, especially for reading, writing, and research.

The popular conception of blindness as a physical reversal of sight but also a possible and mysterious alternative yielding true insight remains a literary and artistic convention. Add the historical perception of the hermit as self-sufficient in both simplicity and wisdom and the archtype is relatively complete.