A conceit of the Romantic period was the sentimental interest in ruins, what the British writer Rose Macaulay might call the “pleasure of ruins.” Wordsworth’s depiction of “Tintern Abbey” and Shelley’s famous poem “Ozymandias” are examples. There is a reminder of impermanence and human fate in reflecting on the ruins of long-ago-and-far-away civilizations.

I once had an idea of creating a calendar, like those ubiquitous themed twelve-month calendars, the ones so quickly marked down for sale after the beginning of January. There are twelve photographs to accompany each month. These calendars are always pleasant and inspirational. I suppose mine would be slightly less so. My pictures would be of ancient ruins representing major civilizations of antiquity, something like this:

- Egyptian

- Babylonian

- Phoenician

- Persian

- Indian

- Chinese

- Cambodian (Angkor Wat)

- Greek

- Roman

- North African

- British (Stonehenge?)

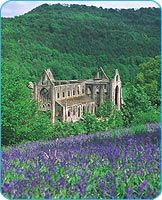

- a medieval European castle, or just Tintern Abbey, with its wonderful purple flowers in spring

There is a reason why ruins of antiquity rather than contemporary ruins would be cited, and even the Romantics would have understood this. We have a plethora of contemporary ruins, made not by the passage of time but by human iniquity (not that violence and power did not exist in antiquity). One could cite such ruins of today: Dresden, Hiroshima, Baghdad … this list could go on, of course.

There is always a fine line between sentimentality and moroseness, between information and morbid curiosity, between moral persuasion and the cloyingly didactic. Reflecting upon ruins of antiquity can be an historical exercise, like reading historical fiction, or a philosophical musing on the passage of time. But the same exercise is made to be political and controversial when the object of reflection is contemporary. Yet the point of both exercises is the same. We ought to conjure the same mingling of moral and intellectual insight from the past as from the present: that the culture around us is destined to pass away even as we dwell in its presence and wrestle with the moral confines of its ignorant architects and its built-in impermanence.