Gregorio López, Hermit of New Spain

The life of Gregorio López

(1542-1596) is known from a biography by Francisco de Losa

(1536-1634), a priest who met López in Mexico and stayed with him until

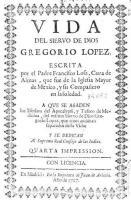

the former's death. Losa composed La vida que hizo el siervo de Dios Gregorio

López, en algunos lugares de esta Nueua España, first printed in

Mexico in

1613. The

biography was popular enough to be reprinted in Madrid in 1642, and in

Paris (1674), Cologne (1686) and London ( 1675). The English edition was titled: The

Holy Life,Pilgrimage, and Blessed Death of Gregory López, a Spanish Hermite in

the West-Indies. An American edition was printed by John Eyre of New York in 1841, with editorial comments demurring from appearing to

inadvertently recommend eremitism to the Christian reader. The edition was

titled The Life of Gregory López, a Hermit in America. An nearly exact

retelling of Losa's biography is A Life of Gregory López by Francis

Cuthbert Doyle, published in London in 1876.

The life of Gregorio López

(1542-1596) is known from a biography by Francisco de Losa

(1536-1634), a priest who met López in Mexico and stayed with him until

the former's death. Losa composed La vida que hizo el siervo de Dios Gregorio

López, en algunos lugares de esta Nueua España, first printed in

Mexico in

1613. The

biography was popular enough to be reprinted in Madrid in 1642, and in

Paris (1674), Cologne (1686) and London ( 1675). The English edition was titled: The

Holy Life,Pilgrimage, and Blessed Death of Gregory López, a Spanish Hermite in

the West-Indies. An American edition was printed by John Eyre of New York in 1841, with editorial comments demurring from appearing to

inadvertently recommend eremitism to the Christian reader. The edition was

titled The Life of Gregory López, a Hermit in America. An nearly exact

retelling of Losa's biography is A Life of Gregory López by Francis

Cuthbert Doyle, published in London in 1876.

Because Losa presents the biography in a straight-forward chronology, summarizing the content of each chapters is sufficient to convey known facts about López and the author's insights. Although intended to edify and popularize, Losa does not use any particularly hagiographic devices. The work is a simple and pious tale of a hermit.

The chapter headings are those of Losa. Quotations are from Losa.

Chapter 1. His birth and employment till he was twenty years of age.

López was born in Madrid in 1542. He told no one of his family origins or kin, suggesting that he was an orphan or had assumed a borrowed name, leading to speculation about whether his background was of nobility (given that his manner was "genteel, noble, and full of humble gravity," says Losa). López had no formal education. Apparently early imbued with religious interest, López had run away as an adolescent to a monastery. Because of his noble character, he was sent to court, probably as a serving youth, but one day he decided to quit the world.

Chapter 2. His voyage to New Spain.

López arrived at Veracruz, Mexico, in 1562, at the age of twenty. He brought with him a sum of money but promptly gave it away. López left for Mexico (that is, Mexico City), where he worked with a notary a while before completing his plans to travel to Zacaticas in the valley of Amajac, home of the Chichinqui Indians. Along the way, however, López stopped at a farm called Temaxeco, belonging to a Captain Pedro Carrillo de Avila. To Carrillo he announces that he is seeking a hermitage and intends to retire from the world.

Carrillo offered him men to build him a little house in the place which he had chosen. He thanked the Captain but did not accept the offer, only expressing leave to build it himself. With his own hands, and with the assistance only of some Indians there, López built a little cell. ... Thus he entered in his twenty-first year upon his solitary life.

From the moment that López abandoned himself in fervent love to whatever it should please God, he felt the sensible effects of his assistance, and began to walk valiantly and with a great pace in the narrow way of penitence, never looking back, never stopping, not losing sight of that light by which it pleased God to guide him.

López adopted ascetic austerities: sleeping on the ground, using a threadbare quilt against the cold, laying his head on a stone as his pillow. He ate one daily meal of primarily parched corn and some vegetables, and "never tasted flesh" or ate with guests. Indeed, he "never went out of his cell to divert himself, or even to entertain himself with a good neighbor." López followed the seasons, never using a candle.

Chapter 3. The conflicts he sustained, and the assistance he received, whereby he was more than conqueror.

This chapter describes the hermit's spiritual combat with demons, analogous to the deeds of the early Christian desert hermits. And, like the Orthodox hermits' use of the Jesus Prayer, López devised his own: "Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven, amen, Jesus!"

Chapter 4. God exercises López in another manner; he removes from the Valley of Amajac.

After three years at Amajac and the hospitality of Captain Carrillo, having endured local suspicion as a non-attendee (of Mass and church services) and possible heretic, López moves to the village of Alphonso d'Avalos, "lodging in a place planted with trees." Here he eats only milk and cheese, spending two years in solitude there, when a Dominican priest named Dominie Salazar convinces him to accept a cell in a monastery in Mexico City, but apparently that, too, was temporary.

How poor so ever he was at that time, he never asked alms of anyone; but entirely abandoned himself to the providence of God, having nothing to live upon but what was given him without asking. And if nothing of this was left, he labored with his hands till he had gained more.

He often worked in his little garden, but what grew there he gave in charity to those that passed by. Sometimes every day he spent in reading the Holy Scriptures and particularly the epistles of St. Paul. ... [The demonic assaults continued, so that] he did not want for enemies in the world, any more than in solitude, but in all these things he was more than conqueror.

Chapter 5. He goes to Mexico, thence to Guasteca, and falls sick.

Though López visited Fr. Dominie, he returned to Guasteca as "most proper for his design as being wide and thinly populated and abounding with wild fruits." Here he made his hermitage, where the food was fruits, roots, and herbs. Here, too, López committed himself to scriptural study and wide readings of ecclesiastical as well as profane authors.

But López suffers a debilitating "bloody flux" and the priest of the town, Juan de Mesa, takes him in to heal him. Thus began a pattern of illness and recovery. He was weak and "would have returned to his solitude" but stayed with Mesa -- who provided him a room -- for four years

Chapter 6. He goes to Atrisco, and thence to Mexico.

Francisco de Losa (the biographer) first hears of López from Mesa. But López is restless with apparent attention given in the locale to himself as resident hermit, and leaves for Atrisco, where he encounters Juan Perez Romero, who gives him a room in his house, plus a new brown robe -- the last he would wear. Here López is again the object of critical scrutiny, and reported to the archbishop, who, however, ignores the reports. López stays with Romero two years but then announces his departure, "leaving both him [Romero], his family, and his neighbors swallowed up in sorrow."

Though he finds a small church near Testuco in which to reside, living seven months in anonymity, sometimes days without food, López again encountered suspicions:

His very uncommon abstinences and manner of life was then matter of edification to some; others suspected all was not well, and others concluded he was a secret heretic.

This time the archbishop dispatched an agent to report about López, but the investigator returned with admiration at the knowledge and insight of the hermit.

Chapter 7. He goes to the Hospital of Guastepea; his inward and outward exercises there.

After two years at Testuco, López had again fallen ill of stomach pains and colic. He goes to the hospital of Guastepea in 1580, where he is cared for by Brother Stephano de Herrera. As the hospital was well funded and served patients from throughout the region, López was given a room and allowed all privilege.

His routine was to keep his chamber until noon, whence he would emerge with a pot of water to warm in the sun and take his meal in silence in the refectory. Afterwards he would converse on spiritual topics with the table guests and visit the sick, retiring to his room until the next day. "As much as he loved solitude, he never shut his door against any who came for spiritual relief or comfort," notes Losa. López soon became famous for his spiritual counsel, and took time to compile a book of remedies, which was later much consulted.

It was probably during this period that López composed his Declaración del Apocalipsis, a commentary on the last book of the New Testament. But he is better known for his book El tesoro de medicina, an exhaustive compilation of herbal and plant remedies that came to his knowledge among the Indians as well as the hospital staff.

Chapter 8. A severe illness obliges him to return to Mexico, whence he retires to St. Foy.

While apparently yet at the hospital, López contracted "purple fever" and is barbarously bled fourteen times, nearly dying. He was diagnosed with inflammation of the liver and recommended to move for a change in air. López travels to the town of St. Augustine, where, however, his newfound acquaintance Francisco Losa finds López too weak to stay alone. Losa moves him to his residence near Mexico City. After several months, still sick and without appetite, Losa takes him to St. Foy (that is, Santa Fe, but not the city in later New Mexico) in 1559, again not far from Mexico City, where López was to remain the rest of his life.

At this point, Losa can more carefully observe the piety of his charge, and the biography focuses on this aspect. So edified is he that Losa retires from his pastoral duties to accompany and observe his friend.

I then observed both day and night all his actions and words with all possible attention, to see if I could discover anything contrary to the high opinion which I had of his virtue. But far from this, his behavior appeared everyday more admirable than before, his virtue more sublime, and his whole conversation rather divine than human.

Losa notes a typical day. López would rise, wash, read a little, then fall into a "recollection": "All one could conjecture from the tranquility and devotion which appeared in his countenance was that he was in the continual presence of God." They would dine at one o'clock, afterwards engage in conversation or Losa might read aloud as a recreation. Then López would return to his room until the next day, though sometimes he received visitors; in his last years the visitors were often ecclesiastics, the learned, or the nobility, going away much edified. López's routine remained not to use a candle, and he retired by about 9:30 in the evening. Towards his last years he had reluctantly accepted the sheepskin quilt offered by Losa, and a bed rather than the floor. In any case, López seldom slept more than a few hours.

The remaining chapters describe the person and character of López, with few events transpiring.

Chapter 9. The knowledge which God infused into his mind.

Chapter 10. His skill in directing others.

Chapter 11. His government of his tongue, and his prudence.

Chapter 12. His patience and humility.

Chapter 13. His prayers.

Chapter 14. His union with God and the fruits thereof.

Losa attests to the vast knowledge of López, of ecclesiastical and profane history, ancient to contemporary, of astronomy, cosmography, geography, botany, zoology, anatomy, medicine, and botanicals. These topics did not distract López from his spirituality, however, for he told Losa, "I find God alike in little things and in great."

But his spiritual discernment was keen, and Losa says that López "saw spiritual things with the eyes of his soul as clearly as outward things with those of his body, and had an amazing accuracy in distinguishing what was of grace and what of nature." For this López was often consulted by visitors as if he was an "oracle from heaven, as a prodigy of holiness." One can imagine how this edified Losa, for in 1579 he began writing about López, even while yet a rector of a large parish in Mexico City.

Losa asked López's advice, too. He asked him if he (Losa) should "live in some solitude as a hermit" as his friend had. López answered him "Remain this year a hermit in Mexico" -- that is, be a hermit in the city, in his present residence. By this, too, López meant that Losa could achieve solitude through austerities, prayer, and recollection. Losa was to remain in his office for six years before finally retiring to share full-time his house with López, finally leaving with López for St. Foy. There they lived until the death of López seven years later, and there Losa remained in solitude for twenty years. In 1612, sixteen years after López's death, and himself 84 years old, Losa wrote the biography.

Among the virtues of Gregorio López was his mildness, patience, and humility -- though he must have suffered greatly from his physical pain. He never judged others: "For many years I have judged no man but believed all to be wiser and better than me. I have not pretended to set myself up above others or to assume any authority over others."

López never complained, and Losa says, "I never heard him speak one single word that could be reproved." His conversation was never but "useful and spiritual," though he preferred silence. López used to say that "My silence will edify more than my words" and "I see that many talk well, but let us live well." Ultimately, however, López no longer identified with this world: "Ever since I came to New Spain I have never desired to see anything in this world, not even my relations, friends or country." Less so was he interested in seeing visions or angels.

Over the course of time, notes Losa, López's prayer evolved from acceptance of God's will to a conscious act of love of God, to a devotion to and imitation of the person of Jesus. He told Losa::

The eyes of the true man are always fixed on Christ, who is his head, and the soul that is touched with love of God is like a needle that is touched with the lodestone always pointing to the North. Thus, in whatever place a truly spiritual man is, and in whatever he is employed, his eyes and his heart are always fixed on Jesus Christ.

In practice it was a disengagement from the world. Losa says, "His soul appeared to be disengaged from all things else by a pure union with God." And as López said to him: "It is much better to treat with God than with man."

The sickness that had dogged López returned one last time in 1596. He lost all appetite and could swallow only liquids. The bloody flux would not stop, and he grew progressively weaker. He told Losa that he had entered "God's time" and his comportment would consist in doing and not in talking. Losa records that "I never perceived in him during his whole illness any repugnance to the order of God but an admirable peace and tranquility, with an entire conformity to His will. All his virtue shone marvelously in his sickness, particularly his humility." López died in July 1595 at 54 years of age, 34 of them spent in the New World.

Doyle recounts (not in Losa) some miracles attributed to López after his death. Due to the unflagging efforts of Losa, Gregorio López was eventually named "blessed" but was never canonized, perhaps because he was not a priest.

Conclusion

Gregorio López was a simple person but an unusual one for the New World in this era. Blinkoff insightfully calls López a "model of pious masculinity for laymen noted for their ambition, greed, and violence." Undoubtedly eremitism as a form of renunciation and disengagement was, in this era, more powerful in its implications for life and society than standard ecclesiastical power, let alone temporal power. The reclusive life of Gregorio López continues to offer a unique model for not only a personal ethos but in its relationship to indigenous people, to nature, and to spirituality.

¶

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

In addition to the primary works cited in the first paragraph, a useful modern addition is: "Francisco Losa and Gregorio López: Spiritual Friendship and Identity Formation on the New Spain Frontier," which is chapter 6 (p. 115-128) of Colonial Saints: Discovering the Holy in the Americas, 1500-1800 by Allan Greer and Jodi Bilinkoff. New York: Routledge, 2002.